“She morally shaped me. She’s like a third parent.”

Nic Knight gushes when describing Anna Scher’s impact on his life.

Knight joined the Anna Scher Theatre in 1987, aged six, and has since forged a successful career in the film and theatre industry as an agent, as well as recently co-producing the British film ‘Sumotherhood’.

His relationship with Scher, however, embodies a consistent theme among those who have felt her maverick presence.

Born in the Irish city of Cork to Jewish Lithuanian parents, Scher dreamed of becoming an actor when her family moved to England in her teenage years. Her dentist father halted her ambitions, however, insisting she found a “real job” — which led her to compromise by attending a teacher training course in north London. In 1968, she began teaching drama classes at Ecclesbourne Junior School and immediately discovered her raison d’etre.

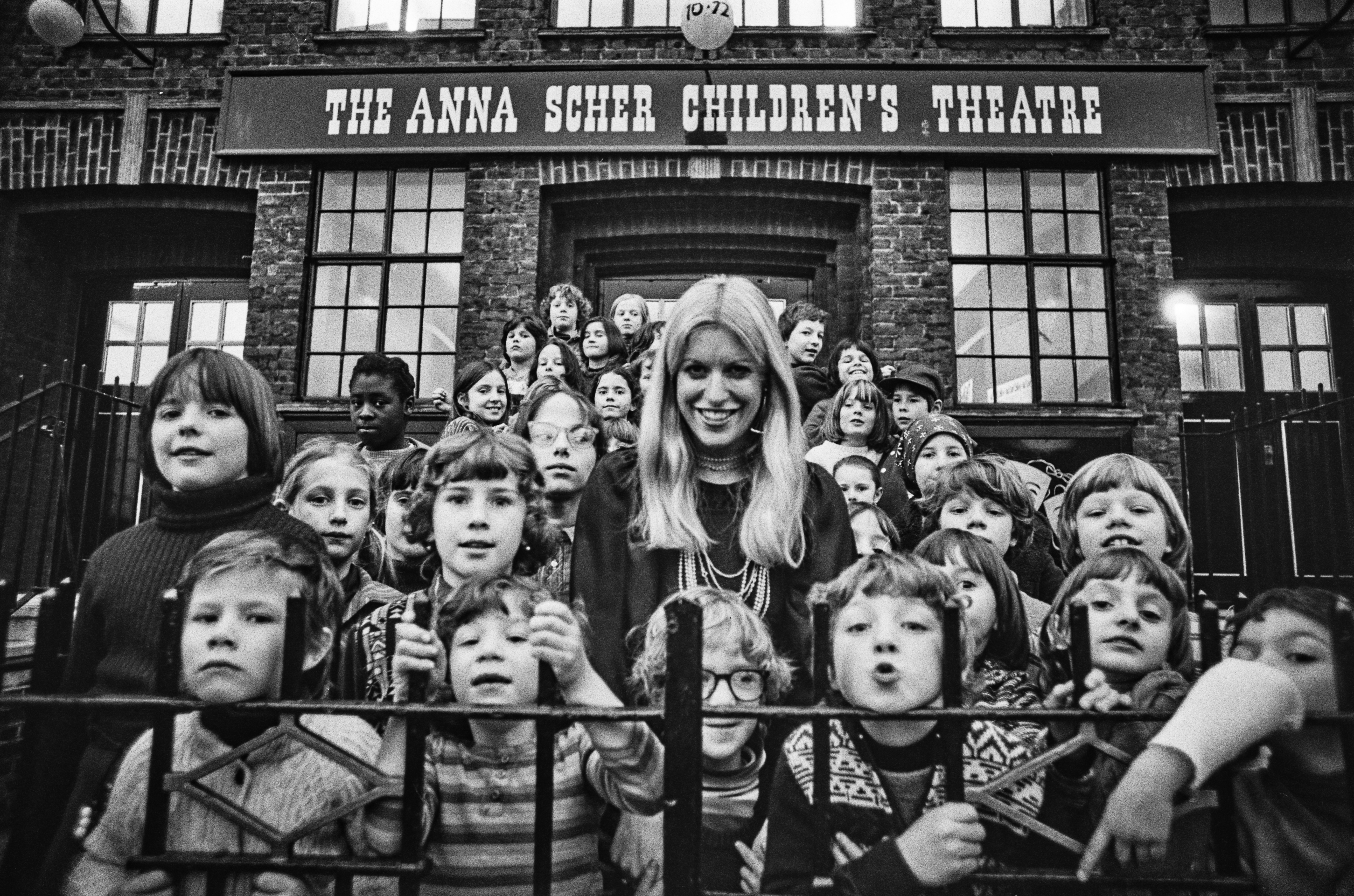

It was only a short time before the class outgrew the school and two years later she moved to a nearby council hall. Yet, her enthusiastic pupils refused to leave when they progressed to secondary school. As the junior classes became flooded with older pupils, the lessons moved into an old Baptist church on the leafy Barnsbury Road in Angel, Islington — with workshop students ranging from children to adults.

The Anna Scher Theatre, established as a charity and charging 10p per class, quickly became a beacon of pride for the local community as Scher’s magnetic personality attracted students of all ages. Classes ran in the evening and on weekends, with waiting lists for places reaching up to five years — rivalling the prestigious boarding school Eton.

“As soon as your kids were born, you did two things,” Knight says. “You had your children registered at the birth certificate office and you put their names down on Anna Scher Theatre’s waiting list.”

And it was Scher’s accessible teaching method that set her apart.

“This very affluent area (Angel) now was literally a bomb site when she arrived in the late sixties,” Knight says.

“She came across improvisation as a teaching technique because the illiteracy was so serious in the area that she couldn’t do scripts.

“The kids couldn’t read and many of the adults as well so she had to find another way.”

Over the last 55 years, Anna Scher has been synonymous with notable working-class actors from north London. Martin and Gary Kemp, Kathy Burke and Pauline are among the countless stars to have learned their trade with Scher. In more recent generations, Daniel Kaluuya and Adam Deacon attended her classes, with the former thanking her when collecting his 2018 BAFTA Rising Star award.

Beyond those in the limelight, it is the transformational impact she has on every student that shines brightest.

“She changed people’s lives,” says Knight. “For every 100 famous, well-off students there are about 15,000 families she has changed for the better because she stopped them going down the wrong path.”

“She put the emphasis on that person to say, ‘This is your choice. Just because so and so is doing this or doing that doesn’t mean that you have to do it, you know better than that.’

“She would say, ‘I expect better from you. And I don’t care if anyone else does. But when you’re here with me, you behave in the right manner.’

“When someone cares for you and values you that way, it changes your own self-worth and belief.”

Dickon Tolson, a former pupil and professional actor who now facilitates lessons at Anna Scher Theatre, resonates with how the school offered a sanctuary for working-class children.

“I grew up in Hackney in the ’80s and it was really quite a brutal environment,” Tolson says.

“I was getting beaten up outside of school most days of the week.

“Once or twice a week I started coming to these classes and found it really calming. It was therapeutic that somebody else believed in peace and not in fighting. It kind of validated how I wanted to see the world.

“It just gave me so much confidence, (it) improved my communication and conflict resolution skills. It allowed me the lateral thinking that there’s another way to be. There’s another way to exist than cussing each other’s mums and beating each other up.”

Scher’s emphasis on morality and improvisation offered a distinct lens to observe life, which was worlds apart from the formality and finesse of traditional drama schools.

More importantly, the affordable pricing made it accessible to all those who did not have the privilege to attend such institutions.

“So many people have become well-known of the back of AST and the fact that it’s affordable speaks volumes,” says Anna Kleanthous, a personal friend of Scher who oversees the school’s operations.

“A lot of actors have had that experience of going to drama school, really expensive places, and we’re very inclusive of the local area, communities and families.”

“Anna (Scher) hates the word stars but a lot of these people that have made it started literally from coming to an after-school club.”

Visiting the Anna Scher Theatre, it is difficult not to be enamoured with the passion and joy that burst out of every class. While lessons are now held in a quaint room at the back of Saint Silas Church — a stone’s throw from the previous location — step inside and there is a Narnia-esque portal to a world of inspiration.

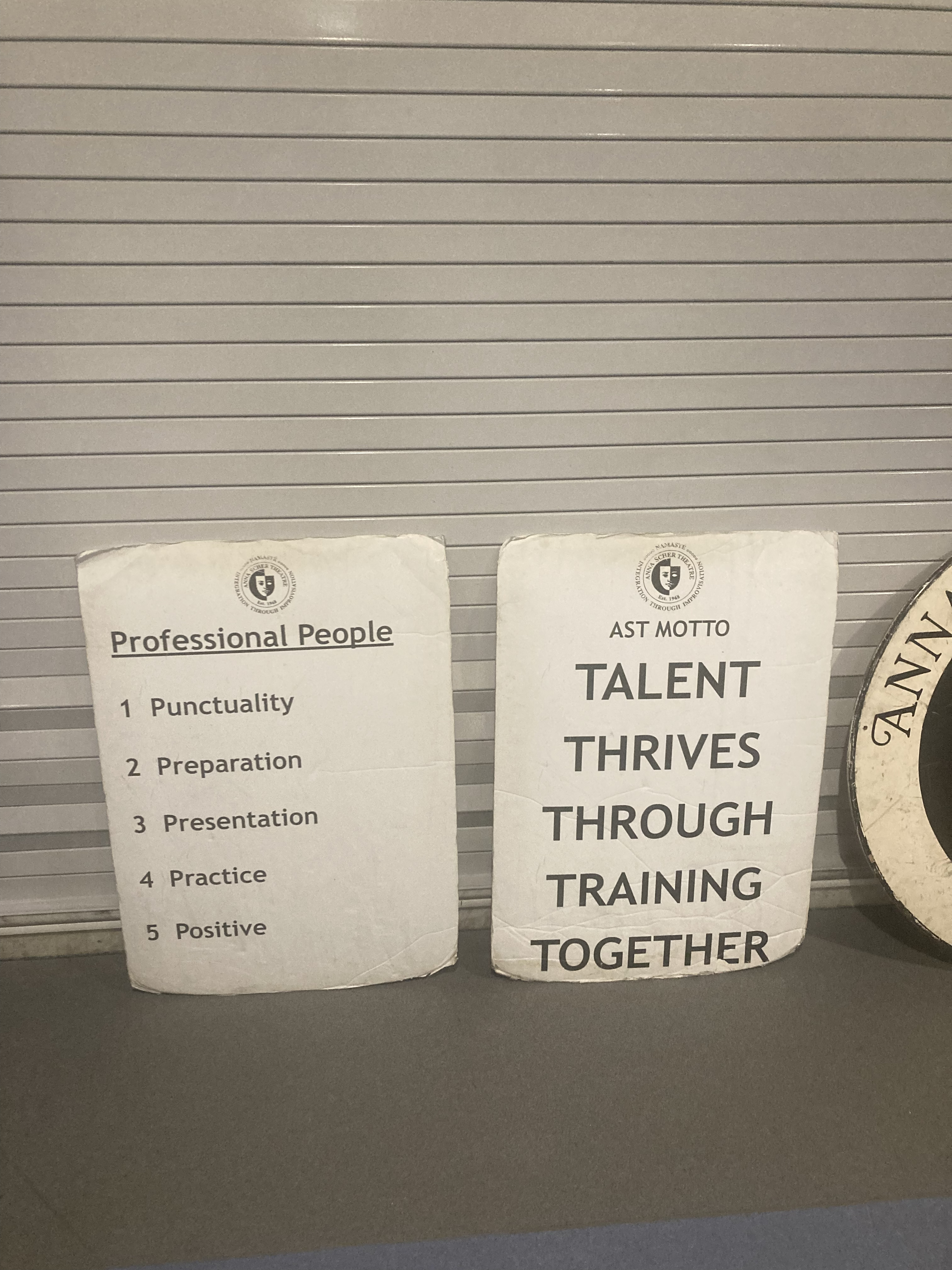

Motivational teachings and disciplinary reminders are dotted around the room, and every class follows an identical format. After paying their dues in cash — £10 for adults and £7.50 for juniors — students form a circle as upbeat entrance music is played through a speaker. As part of a physical warm-up, one-by-one students take turns moving to the centre of the circle and showcase a dance move that the rest follow. The session then transitions to preparing vocal chords through songs accompanied by a pianist. After, students recite a weekly quote and “Winston word” — an ode to former British wartime leader Winston Churchill who claimed to have learned a new word every day of his adult life.

The class returns to its circle as students share facts about themselves, to help integrate any new members, followed by revealing a more personal experience, by answering theme-based questions, such as “who you had a blazing row with”. With revelations taking a humorous or therapeutic turn, the class are then instructed to form small groups. Each group is asked to act out a short scenario related to an initial prompt, as the rest of the class watches intently and provides feedback.

Classes are then closed with the recital of a poem, often a personal favourite of Scher’s, or a performance from experienced members.

“The people I was acting with were really quite rebellious and full of diverse personalities,” says Tolson.

“We were often doing improvisations about quite adult material. You’d have someone acting like a drunk dad, somebody being a disapproving mother of a teenager who just got pregnant.

“And then you had this woman (Scher) who was very strict on discipline and would basically be delivering the same workshop every week.

“So, you had to find freedom within a very strict framework. How could you stretch those boundaries? You had to be inventive and imaginative within the framework, which actually makes you quite creative.

“It’s a bit like a school uniform. If it is just the same, you should all look the same except you find little ways of differentiating yourself.”

The ingenuity taught by Scher is a key factor in her pupils’ success when auditioning for TV roles.

“It’s the believability that gets drummed into you,” Knight says.

“It’s the honesty and the constructive criticism — it gets people to be an extension of themselves.

“And that’s just brilliant acting.”

“At first there were rich kids playing working-class kids, but when we came on set (for auditions), boy did they know we were on set,” Tolson adds with a broadening smile.

“Looking back, we were just so highly spirited and we kind of took over. We had the ability to be natural in front of camera and the ability to apply a technique to our characterisations. We were in our environment.”

While Scher has stepped away from teaching since classes returned after COVID-19, the sessions continue to mesmerise students under Tolson’s supervision.

Graham Farrell, a long-time attendee, says, “It’s a safe space. There’s an acceptance of difference and putting people from different backgrounds together which produces a kind of magic I can’t explain.

“When it finishes, I think, ‘bloody hell, it’s over. Can’t we drag it on a little bit longer?”

Cheryl Ward, another attendee, recognises how Scher’s inclusive attitude continues to be embraced.

“No matter who you are, whether you’re quirky, whatever thoughts you have, if you have additional needs, if you’re loud or quiet — Anna Scher’s just embraces everybody,” she says.

But just how did Scher manage a group of diverse individuals, including young children from difficult upbringings?

“She was fiercely strict,” says Ward. “You couldn’t even be two minutes late to class. No chewing gum. There were no excuses really.”

Tolson’s decades of training allows him to seamlessly recite Scher’s teachings: “The thing that I’m really bad at which I don’t exercise enough — and she was really hot on — is discipline. It takes dedication, determination and drive, and she is such a taskmaster.

“And if you were late, well, punctuality is the politeness of kings.”

“I think that’s why the parents loved her as well because it was someone else telling off their kids,” Knight laughs.

Ward continues: “She wasn’t as strict in more recent years, but she’s still warranted so much respect and adoration from everybody, she didn’t even make people do it. It’s just her nature.”

Scher’s integrity is a prevailing theme and, along with her pupils’ fame, she gained international recognition for her peace work.

In 1979 she was invited by the Northern Ireland Arts Council to set up peace drama workshops in the then-troubled country. Her reputation continued to garner attention and she undertook further visits to Rwanda, working with Tutsis and Hutsis, to Bosnia with Serbs, Croats and Muslims, as well as the Israeli village Neve Shalom (Oasis of Peace), where she taught Jewish and Arab children.

Back in north London, Scher became fondly known as the ‘Angel of Islington’. Even society’s elite — including former Prime Minister Tony Blair and politician Jeremy Corbyn — chose to send their children to her classes instead of rival drama schools.

At the turn of the century, however, Scher faced a gut-wrenching setback. Having taken sick leave from her acting school after suffering a bout of depression, she returned to discover that she had been barred from teaching at the school she had run for over 30 years. The board of trustees later informed her that if she wanted her job back, she would have to interview for it. They then told her she could only return on a set of conditions, which included not advancing issues such as peace or anti-discrimination studies.

The tragedy inspired Scher to open her own rival school, where classes are currently based.

“Other people wanted to go in a different direction, and she wanted to stay true to herself,” says Kleanthous.

“You’re trying to then compete with this amazing institution that you’ve created yourself, but you’ve been whitewashed out of your own,” Knight adds.

“Myself and a few others would have loved to do a legal case for her and push for a lot of stuff,” he said.

“But Anna didn’t. She realised that the fight had hurt her so much. So much that it wasn’t something she wanted to go through again and we have to respect her wishes.”

Scher did manage to regain the naming rights to her school in 2008, with her former institution renamed the ‘Young Actors Theatre’.

The damage had already been done, however, and many prospective pupils continued to be redirected to the previous institution during online searches.

Knight despondently notes, “It was like starting from scratch”.

“Covid was also very tough. It does make me sad that this isn’t more commercially viable and that Anna could be very comfortably off. Money was never Anna’s thing anyway.

“But what’s more important to her is the legacy than having the old building. People like Dickon carry on the best they can to continue the amazing work she does.

“We’ve tried to continue the class the way she was doing it, the way she always has done it, as the method is brilliant.

“What the school has been — and become more of recently — is actually a place for people that feel excluded in one way or another.”

“There’s a real richness to that.”

Despite the altered exterior of her classrooms, Scher’s magnetism has left an indelible mark in Islington.

“Martin Luther King’s daughter, even his wife once came to our little theatre to watch us,” Tolson says, frantically waving his arms in nostalgic excitement.

Beyond her star-studded drama school guests, Scher invites friends to her home — located a few streets away from the drama school — where she lives with her husband and fellow drama teacher Charles Verrall. She sits with friends in the ‘summer room’, which overlooks her garden as they enjoy tea and homemade cake.

“I was at Anna’s house once and she played me a message on her answering machine from Archbishop Desmond Tutu,” Tolson reminisces.

“This was one of the most peaceful, lovely men on the planet, so you can see how highly she is considered by these beautiful people. And he went on for around three minutes raving about Anna’s banana cake!

“It shows the respect and the regard in which she is held. That, for me, says it all.”